In•Humanity

“To be human is to be one of many. I am one individual human; because I am human I understand the many…”

“…All of humanity includes a very large number of individuals. The 7,500,000,000 people that live on the earth today are only a mere 7% of all humans to ever walk the earth. As individuals, we tend to categorize ourselves into smaller and smaller groups. It helps define us. I am female, I am Christian, I am Gen X, I am American, I am heterosexual, I am upper-middle class, and so on. Our categories make us feel understood, and safe. They create a comfort zone from which we judge the world. But they also insulate us from the larger reality of being part of the human race. When we categorize ourselves, we tend to categorize others. When a person becomes classified and labeled as a group, they are stripped of their individual story. This dehumanization makes it easier to shun, insult, ignore, and injure.

“Stories are the tools that can pierce the walls of classification. Stories remind us what it means to be human. We understand them because we are human. And telling them strengthens our humanity (singular and plural). A story can bring me out of my self-constructed walls into a dusty courtyard in the Middle East where a god-fearing mother has just lost her child and whose own life is threatened. Because I have children of my own, I begin to understand her pain. Because I have feared for my children’s lives, I understand some of her fear. Because I have traveled into the foreign unknown, I understand her vulnerability. Now her actions make sense. Her gracious and generous nature has added significance. Real stories of real individuals are more powerful than statistics because they rely on shared experience and open the door for empathy.

“When we look someone in the eye, it is harder to hate them. When we hear their story, we begin to understand. And understanding is the first step towards empathy and a better world. Empathy requires not just listening, but a setting aside of our own narrative. We let go of prejudices and preconceptions. We put on another’s shoes, enter their world, and feel as they feel. We begin to see eye to eye. The more we hear, the more we understand. And when the story is heard, we step back into our own world that has now unexpectedly enlarged. Empathy inspires kindness, understanding, sacrifice, and compromise. Empathy can create bonds that reach through cultures, religions, borders, and generations, bonds that take humanity from the individual and biological meanings into the realm of collective and eternal.

“These drawings and paintings represent an effort to bring you into another’s story. They are glimpses into the lives of refugees from the Middle East and Africa. They are only a few of millions who feel rejected, ignored, and forgotten. They want to tell their story. I want to show who they are. If you cannot stand literally face to face, I hope you will take this opportunity to look into their eyes and listen. Discover that their stories are actually all a part of our Story.

“To be human is to be one of many. To show humanity is to take many and become one.”

Elizabeth Thayer

Everyone has a story: sentences and chapters that explain why we do, say, think, and feel. A story is an invitation to understanding and a doorway to Self. But what if parts of a story are too painful to share, too dangerous to open? There is a mutual fear that prevents a mutual hope of understanding between people. Patient sincerity and willingness to listen, unprejudiced, can help create a safe space where connections happen. May we all have and be that person for someone.

Aeham

18 x 24”, oil, $4000

I met Aeham in the summer of 2016 in Germany. Despite having just travelled all night by bus, he was open and so friendly, with a smile that lit up his whole face. After less than a year in Europe he was speaking enough German and English to have a good conversation, and even make jokes. But when he told us about his life in Syria and his escape to the EU and his family still in Yarmouk, his eyes got so deep and sad I thought the spark would never return. And then he played his music for us. It is a sound that will stay with me forever.

Aeham comes from Yarmouk, a mostly-destroyed suburb of Damascus in Syria. When bombs started falling in 2014, Aeham pushed his piano on a vegetable cart into the destroyed streets and played music. With a friend, he would make food and hand it out to survivors. He explained,

"Music makes us happy. Full of energy and full of lovely things in the heart but it doesn't make anything for the stomach. In Yarmouk we couldn’t make enough falafels to fill stomachs because we have 100,000 people. But we can play music for 100,000 people…”

Yet music didn’t make the streets safer. Aeham was hit and his friend was killed by a sniper as they served falafel to the neighborhood. His piano was blown up in the street by militants.

"There has been a safe place [in Yarmouk] made for children underground. A small place for happiness because there has been a lot of sadness, a lot of dying there. I have a friend who makes music, makes jokes with the children.... it helps the children to not stay in the street because it's very dangerous...a sniper killed [a child] when she played piano with me [in the street]. She was twelve years old. Yes, it's good to play with the children under the ground, not outside."

When he realized he couldn’t wait out the war, Aeham made a 2,400 mile journey to Germany, hoping to find a safe place to live and send for his wife and two children. He began to perform concerts to benefit war-torn Syria.

“I have a lot of memories from music. I didn't [used to] play a lot of pain music. Now I play a lot of pain music because I have pain. I talk about Syria and play music, tell the people my story...but it is not changing anything. In this dirty war nobody can have a decision. You die or flee. You have it only one way. Nobody in Syria is safe.”

Aeham has since been reunited with his young family in Europe and continues his work for those affected by the Syrian conflict.

I wanted to somehow embed Aeham’s music into my portrait of him because it is so expressive of his story. I painted a QR code in the bottom corner of the portrait, which, when scanned with a mobile device, will take the viewer directly to a sound recording of Aeham’s music, making this a collaborative artwork in a way. I hope this is symbolic of how people can come together across oceans and cultural divides to make something meaningful and even beautiful.

Ualda

“She was going to be married to an old man against her will and I (her husband James) decided to go to her hometown and we escaped together to Kabul, where we got married. We belong to different ethnic groups and nobody in her family accepted our relationship. She had no consent from her parents to leave with me and they would say I kidnapped her. Her brothers tried to find me, because this is something very shameful for the family.”

Ualda comes from a world where it is dangerous for a woman to be educated or outspoken. Women have very few rights or freedoms. So I wasn't surprised by her apparent shyness. But as I watched her and learned about what she has been through, I understood the quiet depths in her eyes and was touched by her gracious kindness. She ran away and married against the wishes of her family. She lived in constant danger with her husband and their three small children, one of which she lost when he was only three years old. She made a harrowing journey to a foreign country where she does not speak the language or understand the customs. She lives and cares for her family, not knowing what their future might be.

I think there must be a certain pain that only mothers who have lost a child know. Is that pain worse when your child's mutilated body is delivered back to you by the kidnappers? Maybe someday I will be able to ask her, in a common language, and find out what keeps her going. In the meantime, I treasure her example and friendship.

11 x 14”, oil

Sahar

9 x 12”, oil, $500

"My name is Sahar. I left my country because I received a Book of Mormon from a friend and made five or six copies on a copy machine (which took a long time), and gave them to my friends. These were my friends from school. We were always together in class and we grew up together. We always had problems with Islam.

"We studied the book together for one or two months. Then one of my friends got arrested in a park. When the police searched her bag, they found her copy of the book. They realized that it was a Christian book so they took her to the police station, questioned her and tortured her, and they put her in jail. She finally gave them my name. When the police came to our home, I was not there, thank God. I was at my uncle’s house. I could not go back home. I was able to escape from my country.

"I faced many difficulties. I walked all the way to Turkey (over 1600 miles). I had no money. I had to work long shifts in a restaurant in Turkey until I finally earned enough to leave Turkey for Greece, then Serbia, Croatia, and then to Austria. And after that, I came to Germany. I arrived barefoot and in very bad condition.

"[After] I arrived here, I found the father of the person who gave me the Book of Mormon in Iran and went to visit him. I explained to him what had happened to me, told him that I knew his son, and how I received the book from him. After that, he spent a lot of time with me explaining the religion. He introduced me to the church and I was baptized.

"For a year and a half I was in a camp where 150 men and women live together in a sports facility. The worst part, though, has been the endless waiting – especially for a 20-year old girl alone, with no parents. The loneliness grows and turns into an obsession in the heart because my family is not with me. Now that I have escaped my country, I have no one. Here in Germany, they have rejected me, too. I went to court and explained everything truthfully. In spite of that, they want to deport me back to my country. I cannot go back, I really cannot. If that had been an option I would not have put up with these three years of problems and loneliness.

“I will keep trying and implore Jesus Christ to help me in this difficult situation and to guide me in the right path for a good life here."

Hawa

11x14”, charcoal

“My father had enemies in our home country. A man shot him three or four times. It broke my father’s leg, but he escaped. He and my mother took me and my siblings on a journey. We had to leave our home. Every time we tried to cross the border the police caught us and sent us back. The last time we had to walk for seven hours without stopping to sleep. We had to get on a boat and we were on the water for five hours. It was so long. The boat stopped working but some people saved us and brought us to an island. My father is very sick and we don’t have any more money. I don’t know what will happen to us.”

Musa

12 x 16”, oil, $1000

“My name is Musa. My dad was a civil engineer. I am a computer scientist and a graphic designer. And my brother, he’s Down syndrome and blind. He is 17 years old. My mother is a biology teacher. My wife is 23-years-old. She is an artist and painter. She is in the tent with my son. And my son is five-days-old. I am a new father. I am excited and nervous and I just don't know what to do.

“We had various problems [in our home country]. My dad was working in the military. He got attacked and lost an eye. He was in a coma for something like a week. He left the army and was working doing irrigation projects. He got warning letters because his project was internationally sponsored. They said, ‘Don’t come here again. You’re going to die.’

“I was working in the army on a biometrics security program. I was registering soldiers by taking fingerprints, eye scans, etc. from each soldier. I would find who might be terrorist spies and report them to the government. I got attacked two times. The first attack was normal. I was sitting in the car. A rocket came in one window and out another. But I just said, ‘OK, it happens. I am working for the military. I have to get used to this stuff.’

“The second attack was a magnet bomb. I was riding in the car. We were followed by a motorbike rider and he was covered with a big black and white scarf and had something in his jacket. When we came close to a village, he sped up and attached a magnet bomb to the car and then turned into the village. It was maybe five seconds before the car exploded. Two guards who were sitting in the back seat were killed. The driver and I survived. I was thrown through the windshield. My shoulder touched the engine; when I pulled myself up I saw my skin and my muscles were cooking there. Blood was coming from everywhere. I thought I was sweating but whenever I tried to clean up, it was blood. My right hand was not working. I wiped my face with my left hand and said, ‘It’s OK. I am fine.’ And after that I don’t remember anything. When I came back, I quit my job.

“We were a rich family in Afghanistan. We had two cars and a private house. Plenty of monthly income. My dad, my mom, and myself were all working. We are not here for economic reasons. We are not here for vacation. We are not here to have fun. We are here due to safety reasons. I’m educated. I know five languages. We all have skills. We can use them.

“My life is important. My family’s life is important. I shouldn’t have to say goodbye but I did. I don’t want economic support from any country. I just need security. I just need peace. I just need to live. For a time I was playing with life; I was enjoying it, but now life is playing with me. I don’t know what my destiny will be. Or how long I will be staying here. We will see what they will decide for us.”

Nevin

11 x 14”, charcoal, $500

"I am a civil engineer. I was good at my job. I worked for several years with a U.S. company and also the Afghan government. The Taliban found out about me and said I must come and work with them. They would call me, or send warnings. One time, when I was driving from my village to Kabul, they attacked me. They hid in the mountains and fired at my car. They hit the windows, tires and back side of the car. I jumped out and ran. I jumped down a steep ravine to the river bank where I was out of sight of the attackers and ran for a long time. A few months later, I left Afghanistan because I did not want to work for the Taliban.

“I flew to Tehran by plane. From there, six of us were driven 12 hours in one car to Urmia. It was so dangerous; at three or four points we escaped from the police. There, the smugglers kept us for two days in a house that was under construction. There were more than 30 people, including families. We didn’t have a place to sleep, or enough food to eat, or clean drinking water. After two days, the smugglers placed us in cars. In the middle of the trip we had to get in the trunk. It was winter and snow was everywhere. Finally, we arrived in a place between the mountains. We stayed in a garage for hours; it was freezing. At midnight we started our trip on foot. It was very dangerous and also very cold. Several times we hid from soldiers. In the middle of the journey, the smuggler left us and said, ‘You must go that way.’ Nine hours later we walked into Turkey.

“Over many days, we made our way through Turkey to the coast. One night, on our way to the beach, we ran into the Turkish police. We escaped and the smuggler hid us in a house. Oh God, it was so dangerous. We were more than 40 people in two rooms. Several times the police knocked on the door and tried to open it, but we were silent. That night was full of fear. There were many families, also children. We didn’t sleep all night because we were afraid.

“The next night we made it to the beach. They put more than 50 people in one boat. After 1.5 hours we arrived at Lesbos. It was dark and nobody knew where we should go. We walked 3 hours into the mountains and then ran into two aid workers. They gave us food, water, blankets and a place to sleep. We were so happy because after such a long time we had arrived in a safe place.

“I tried three times to leave Greece through Macedonia but was caught. I tried six times to get to Germany by plane. Every time, I was caught and turned back. I decided to go by foot. I took a train to Thessaloniki. From there, I don't know which countries we crossed to get to Germany. The smugglers took our phones and we usually traveled at night. After almost one and half months of traveling by foot and by car, hiding in villages, and sometimes being caught and sent back, I arrived in Germany. Now I have started language training. I hope I can find a good life and that I can continue in my profession."

Firoz

16 x 20”, oil, $3000

"We were very happy in Syria and our lives were good. Our family worked as carpenters. Everyone in my family lived nearby. Then ISIS invaded our village. They began killing people without mercy because we don’t share their religion. They slaughter people in the name of God. They kill so many. They don’t bury them, they just throw them in pits.

“Men are coming from other countries. Some are fighting for Al-Assad and some are fighting for ISIS. They are taking 14 and 15 year-olds and dragging them into the army. It frightened me because I am 13. We have men in our village who saw that ISIS was getting stronger and joined them. Now they seek revenge for past quarrels with others in our village and kill them.

"We left to Turkey to work and to find a safe place. I was planning to remain in Turkey with my parents but when my aunt was preparing to go to Germany, I told my father I wanted to go too. He said, ‘Let’s go. Get your things ready.’ In two or three hours we were on our way. I left with my aunt and her children. My parents did not come.

"We brought things with us to put in the boat but the Turkish smugglers didn’t let us take them. At sea, the waves were crashing on us and there was rain and wind. The smugglers took us halfway and then they left. The waves were high, God almighty!

"We almost reached an island but there was a hole in the boat and we sank. We remained in the water an hour-and-a-half. There were Nigerians in a boat who helped us — God reward them. On the island there were just trees, no people. We made a fire from our clothes to warm up and remained there two days. Fishermen came by and could see us. They told us they could take us to the beach [in Greece] if we would give them 100 euros for every six people. We paid because we had no other choice. Some of us were taken by inflatable boat, about a hundred people. [We then traveled] from Serbia to Macedonia, from Macedonia to Croatia, from Croatia to Austria, and from Austria to Germany.

"I am thirteen-years-old and I worry about my family. My father loves me. My mother has high blood pressure and my father has three bad discs in his back so he can’t work. I want to be with them, but I can’t. I’m worried about my family all the time, every minute. It’s hard without them. They want to come but there is no money. The borders are closed. If my family can’t come here, I would like to go back with them to Syria. We were happy there before ISIS invaded and ruined our lives.

"I wish [success] for those who try to help bring families together. I want to thank you all so much for listening to my story. And may God make you well for listening."

Kamil

11 x 14”, oil, $600

Kamil was born a refugee, as was his father, Akhtar. His Palestinian grandparents fled to Syria in the late 1940’s and raised their family in Yarmouk, a thriving, almost exclusively Palestinian suburb of Damascus. Akhtar became a master granite and marble craftsman and built a successful stonemason business with several stores around Damascus. Kamil and his two brothers learned the craft and worked alongside their father in the family business creating beautiful staircases, tables, countertops and mosaic tile flooring from granite and marble. Kamil loved working with the stone and enjoyed the comfortable life it provided — hunting, fishing, and riding motorcycles in his spare time.

Then everything changed. Bombs destroyed their home, their business, and their beloved Yarmouk. Kamil watched as neighbors and friends were shot in the streets by the dozens. He and his father scrambled to salvage what little they could, then fled with other family members to a camp in Lebanon.

“I’m 24 years old. I have been working with marble and stone for ten years, since I was 15 years old. My family and I fled Yarmouk. There is nothing left there now. Our papers that had everything, our ID’s, drivers license, hunting license - we went back later and it was all gone. Everything in the house was gone, the whole camp had been ransacked, not just my house. All of Yarmouk was stolen.

“We went to Lebanon. We stayed in Lebanon for three years assuming it would end. We were waiting for it to end, assuming tomorrow there would be a peaceful solution, a political solution, an end to this tragic war. But it would not end. We tried working in Lebanon. We didn’t depend on anybody. We could barely take care of ourselves and God protected us. It was a battle. I worked with marble for around a year and a half. I would work for the whole week to get a hundred dollars. A whole week - seven days - for a hundred dollars. From eight in the morning to five in the evening. We would work only to drink and eat, that’s it. There was nothing left over.

“My father and I left; we went to Turkey. We crossed the borders by walking. Then we traveled by sea from Izmir to Greece - in an inflatable boat. We remained sitting in the boat on the sea for five hours. The Turks stopped the boats twice, but God helped us until we arrived. Praise be to God.”

Today, after spending a year living in German camps and learning the language, Kamil and Akhtar live in a small attic room and are still waiting to receive asylum in an overwhelmed, overrun, but open-armed German system. They have both begun apprenticeships in a granite quarry making gravestones. It’s a humble beginning for two men who are masters at their craft but they are grateful for the chance to work and they know they must be patient. They’re making a new beginning and are hopeful.

Walid

11 x 14”, oil, $600

“I graduated in journalism and then I joined the police force. During my four years of service, we shared forces with NATO. They were our advisors. We did joint operations. My job was to film all operations while they were conducted, including opium campaigns and anti-terrorist operations. I was responsible for making advertisements that cultivating opium was bad and had dangerous consequences, and that people should support security forces and NATO forces because they are responsible for providing peace. I had many threats, but I didn't care because I was doing service.

“Some groups were created in the area, groups that would commit terrorism at night. They put silencers on top of the weapons. They used motorcycles to enter among the police. They entered translators' homes and killed them. For every soldier serving the government they would give fifty thousand Afghanis for killing him.

“During my service, I lost many of my friends. Sometimes, during heavy operations, I used to collect the bodies of my friends with my own hands. Some of them have lost their legs. Some of them were exploded in mines. A close friend of mine whose name was Farzaad, the Taliban had caught him under charges of cooperating with the government and advertising against them; they tore his skin apart. When Bahnam was going to the service place from his home, they put assassins in his way. When Pazir was going towards the bank to get money, they killed him near the bank. And Isaad went to the market to buy a CD and listen to music. There were Taliban members inside the store. They hit him directly in the eye with a sniper. They had followed us and shot him from the rooftop. I remember Shahmeer who was responsible for detecting mines. He was engaged for three years. During those years, he said he would go and then he would marry. Then, when we were traveling to [another city], he was exploded in a mine and was killed. When I carried his dead body to his fiancee, she went mad.

“I couldn't take it anymore. After four years of duty I quit and went to my own county. I started a job as an announcer in a local radio. I had this job for two months when warnings started again. They said, ‘You have been in many operations. You have advertised a lot against us.’ They warned that they would attack my family. I couldn’t stay.

“I went to Pakistan. While there, I heard that they had found my family. They killed my father because his son (I) was a police officer. If I went back, I would lose everything. I had to keep going with the money that I had - and I had to pay a lot. The experience I had on the way from Turkey to Greece was really terrible and I couldn't continue the smuggle. Here, I don't know what will happen. When I seek asylum, I don't know what will happen and so far, they have given no answers.”

Fahima

11 x 14”, oil, $600

“My father was a soldier. He lost his two feet when he was fighting and defending his homeland. He died five years ago because his feet kept pouring out filth. I have 3 sisters and 2 brothers.

“After my father’s death, everyone said that, since we had no father anymore, we had no guardian. Thus, we must get married. But we did not want to. They said that girls must not talk at all; girls must not protest. It is not a custom in Afghanistan for girls to talk. They have no right to study and work, they must only get married.

“If my brother-in-law had not helped us escape, they would have forcibly married me off, and they not only would have destroyed my life, but my studies would have been in vain, too. My mother brought us here so that we can have a safe shelter. We had no security there at all. We used to get poisoned for going to school. If we manage to go to a better country, I can study further, and we can live in security.”

Fahima and her family made it from Greece to Serbia, but have been there, destitute and trapped behind closed borders, for more than a year. This is what she wrote after a recent failed border crossing attempt.

“I am so tired from last night. We walked in the jungle all night, until today in the morning. At 7:00 we arrived in Croatia, but police caught us and deported us back to Serbia.

“I am so tired; I feel so much pain in my body. I don’t know what we can do.…. My eyes are in too much pain.

“From Croatia to Italy it costs 400 Euro for one person. We know some families that pay twice as much. If you pay more money you can go a shorter way… If we go by ourselves, we have to pay 400 Euro per person and go the long way.

“I don’t know what will happen to us. It is two years that we don’t have money. We have to wait, but the borders are closed. What can we do? Why did it happen like this for us? I don’t have any more patience.”

Zarrin

11 x 15”, charcoal

“My life was very good in Afghanistan. I was a teacher, an English teacher. My husband was rich; he was a businessman. My children studied in priority school. One day some Taliban members came and stood in front of my school and called to me, “Come here.” I did not go. I shouted. People began coming and they left. Back in the school I told the principal and he called my husband to pick me up. My brother said we must leave the country or we might be killed. It was very difficult for me to decide because I liked my life.

“The Taliban sent many warnings to my husband. ‘Why does your wife go to school and teach children? If your wife goes to school we'll throw acid on her face and take your children.’ And after that my husband decided to leave.”

Zarrin and her husband made the arduous journey from Afghanistan through Iran and into Turkey before crossing the sea to Greece. Over the mountains, they each carried a child while their oldest walked. At one point Zarrin was alone with the children for three days with nothing to eat but snow while her husband left to buy food and travel documents. Then came the worst part - the sea journey.

“When we got into the boat, lots of water was coming in — I thought maybe my children would drown. I’m shouting! The smuggler said, “Go! You must go!” The sea was rough and the boat tipped. It was so stormy! The waves were coming into the boat but the police were coming on shore and when my husband saw, he shouted and we got back in the boat.

“My husband brought a lot of money and I was carrying it. The smuggler said, ‘Everybody, throw your things into the sea. If you do not throw everything into the sea, maybe you will all drown.’ The ship was full of water. Water! I was so distressed I didn’t remember our money in the backpack. The smugglers took all our bags and threw them into the sea.

“When we arrived in Greece, my husband asked, “Where is your bag?” I said, “In the sea.” My husband began shouting and fell on the ground. He was carried into a building. The doctor came and examined him. My family was shouting. My husband couldn’t speak. He couldn’t open his eyes. He couldn’t hear. And he wasn’t breathing. My children were crying and I was crying. After two hours of oxygen and some tablets, the doctor examined him and let him go on the bus into the island. Now he is OK. It was very difficult.

“It is my advice for another person to never come by ship, because the sea is very dangerous. All the time in my dreams at night I see my family drowning in the sea. Sometimes I cry in my dreams. When I sit in the day, I think about the journey, about the sea. I don’t ever want to go back to the sea. Now we don’t have any money here because I lost it. This life is really difficult for me. This is very difficult for my family.”

Running Water

18 x 27” oil, $5000

Their whole lives were destroyed: comfortable homes, communities, families, studies, steady jobs, and hopes for the future. They fled their countries, carrying little but the hope of a safer future with them. Now they wait, paused for who knows how long in tents on the site of an abandoned factory in Greece. Instead of being in school or playing in parks, children come up with ways to stay entertained as mothers find ways to keep them alive and fathers watch for a chance to move again toward safety. Comparatively speaking, it is not the worst place to wait. This camp has the luxuries of a small schoolroom, a medical unit, an electric strip for charging phones, two rows of port-a-potties, a shower unit . . . and running water from a hose for drinking and for washing. For most, running water used to be a common convenience that was taken for granted. Now, like the hope that keeps them going day in and day out, it is a precious, sustaining necessity.

Barbara Kingsolver wrote, “The very least you can do in your life is figure out what you hope for. And the most you can do is live inside that hope. Not admire it from a distance but live right in it, under its roof.” And that is what these refugees do. They cling to hope in an ocean of uncertainty. In the words of Hamed, a refugee in the camp, “Other than hope, we don’t have anything else. Every day the refugees keep praying and nobody hears their voice except God. They are still waiting. But still, we have hope.”

Sima

11x14”, charcoal

“My husband’s father was a public figure. He held a high position in the Afghan state. He was attacked, beaten, and forced to leave his job. Now one of his hands and his feet are paralyzed. Now he cannot walk at all.

“We had to leave. We had many problems. We called a smuggler. They treated us with hate. No sleep at night, no food for days. Turkish police caught and beat my husband. We couldn’t understand what they were saying, but they beat him and punished him. We spent several nights in the mountains without water or bread. It was snowing. It was so very hard. We did not even hope to see the light of day.

“We were crossing a border when the police came and split our group in two. Our three-year-old boy was lost on the other side of the border. He was gone for two days before we could pay a smuggler to get him back to us. It was all the money we had; we were so afraid.”

Sima gave birth to a healthy baby just days after sharing her story with us. After spending more than nine months in Greece, she and her husband decided to once again pay a smuggler to guide them and their four children across the closed borders and up into Serbia—a distance of 470 miles. Since leaving their homeland in 2016, they have traveled over 3000 miles across six countries, and are still without a home.

Shakila

11 x 14”, oil

“People in Afghanistan are recognized as Shia or Sunni by their father’s name. As a girl I was a very good student; however, when I turned in my work, my teachers would figure out that I am Shia and would deduct 10 to 20 marks just because of this. There were also language prejudices. Our government is Pashto and they support Pashto speaking people. Whatever you try, it's useless if you speak Farsi and if you are Shia.

“As a teacher I taught for 12 years. Even now, the school children who should play hurt and insult each other because the religion and language have taught them to. Once a student told me, ‘You are a very good teacher. You are very kind; you teach very well, but Ah… too bad you are Shia, Ah…too bad you are Hazara.’ It was very upsetting that a child would say that. I have so many memories like this.

“There isn't anybody who doesn’t love their homeland; we love our country as well, but we left because on one side there was war and suicide bombings, on the other there were tribal and religious prejudices. I'm proud of the country’s history but now they have destroyed that history. I'm proud of our ancestors for their courage and reputation in the world, but now Afghanistan is nothing, especially for the women.

“Afghanistan is very patriarchal; women's rights are totally trampled. In Islam, the woman has great value, but in Afghanistan she has none. In the constitution, women have equal rights with men; they can study and work, but in reality they have none of those rights. Most women think they must obey their husbands in everything. If he says eat, she must eat. If he says go, she must to go. If she gets sick, she can't go to the clinic until the husband says she can go. I wanted to help other women there - to teach them about their rights.

“I was part of our town’s women’s society. We would inform families about many things, for example, the benefits of vaccination for children. We told them about women’s rights according to the Koran. One day the community leaders caught me and dragged me to the main square. They asked me, “Why do you inform our wives? You made our wives shameless and stubborn like yourself!” They kicked and beat me. They shot me in both knees with a gun. I was at home for 6 months because of the injury and unable to walk for 2 years. All because I wanted to help the women; I wanted to guide them.

“I'm truly exhausted - so much that I can't explain. I'm a diligent woman. I always tried to be independent and always tried to help others, but I couldn't do it anymore. It took us one month to get from Kabul to the Iranian border. We suffered so much there. We couldn’t get a visa to Iran, so we went illegally. We had to pay a lot of money to the smuggler and he left us at the border. We knew it would be a difficult journey, but we had to leave.”

Felix

11 x 14”, oil, $600

“I am from Nigeria and I have a family back home. My dad has seven children. My mom gave him five children. I left home about two months after coming back from a two-year mission for our church. Then my family supported me to go learn and work because of the love they have for me. They gave money to send me to Europe for school to study computer engineering. My family loves me so much.

“I traveled to Congo then to Niger and to Libya. Before we got to Libya, there was a lot of struggling in the desert. They took about 29 or 30 of us in the back of a truck and the smugglers told us if we didn’t sit tight while the motor was moving, we could fall, and if we fell, the driver would not wait. One friend died in the desert. We had to pay bribes to border guards to pass through the land. And we had to pay money to eat. The little we had was expensive. Many women died in the camp where we slept on the ground like slaves. Many people died. A lot. The water we had was pink. We could not drink it because it was rotten. To drink it was to die. Some people, however, did drink it because there was no water. That journey is very, very risky.

“When we reached the sea, we were held captive for money. The Arab people did not want us to go outside or for a walk. They could shoot you or send you back home. I spent nine months in Libya calling my parents every month to get more money. A man kept pushing me for money. My mom sent me money and I had to give it to the man that was pushing people [and they released me]. In Libya, life is no good.

“Government people rescued us when we were on top of the sea [on our way to Italy]. We pushed out five boats; four capsized during the journey. A lot of souls died in that sea. There were people calling for their children — their son, their daughter. The others would lie, "They aren't here; we do not have them. They are not dead." For so long they were calling. Hoping. Not knowing they had died.

“The first day I came to Italy I had a friend, an Italian friend. I told her I wanted to locate a church to go to. She said she would help me find it. I told her I was a missionary. Finally we found one here so from that time I have been able to attend the church.“

Holding On

18 x 24”, oil, $4000

I met Saeedah in Germany and was enchanted by her bright, light blue eyes and sweet temperament. She was living in one home with twenty-six other women and children who had been separated from husbands and fathers somewhere along their flight to safety. They are among the eleven million Syrians who have fled their homes since 2011, hoping to escape the horrors of war and find some kind of peace. It is a crisis that will not just go away. Millions of normal, everyday people are sitting in temporary housing, refugee camps, or worse, waiting for life to begin again.

Like any young girl on the brink of adolescence, Saeedah’s eyes were bright with possibilities, and she was eager to show how responsible and she could be. In the midst of turmoil, violence and upheaval, she and millions of others live in uncertainty but are remarkably resilient and cheerful in bad conditions. They hold up the best they can and cling to the most important things—loved ones, faith, and hope. They are holding on.

Haider

9x12”, oil

[In the words of Haider’s mother:] “My husband’s father was a public figure. He held a high position in the Afghan state. He was attacked, beaten, and forced to leave his job. Now one of his hands and his feet are paralyzed. Now he cannot walk at all.

“We had to leave. We had many problems. We called a smuggler. They treated us with hate. No sleep at night, no food for days. Turkish police caught and beat my husband. We couldn’t understand what they were saying, but they beat him and punished him. We spent several nights in the mountains without water or bread. It was snowing. It was so very hard. We did not even hope to see the light of day.”

“We were crossing a border when the police came and split our group in two. Our three-year-old boy was lost on the other side of the border. He was gone for two days before we could pay a smuggler to get him back to us. It was all the money we had; we were so afraid.”

Haider’s mother gave birth to a healthy baby just days after sharing her story with us. After spending more than nine months in Greece, she and her husband decided to once again pay a smuggler to guide them and their four children across the closed borders and up into Serbia—a distance of 470 miles. Since leaving their homeland in 2016, they have traveled over 3000 miles across six countries, and are still without a home.

Nagia

16 x 20”, oil, $3000

[The words of her sister:] “My family went to Iran because the Taliban was searching for my family. My uncle, my father’s brother said, ‘I can’t be part of the Taliban. I can’t cut people’s hands or heads off.’ And now it’s been six years, I don’t know where my uncle is.

“Three times my father went back to Afghanistan and tried to find his brother. And a fourth time he went back to Afghanistan looking for his brother again. And when he came back he said the Taliban tied his hands. For one week he was tied in a chair and they beat him. And they told him they wanted him to witness how they would kill his family. And then they would will kill him.

“The Taliban went to my father’s uncle and aunt. Their boy, he was 21-years-old and was getting married that day and they cut his fingers until he died. And his took his eyes out and gave them to his wife. His wife was so angry and so sad, she cried a lot.

“My father, he came back to Iran and for the fifth time the Iran police sent us back to Afghanistan and my father was scared a lot. But again we came back to Iran; we were smuggled. For one week we went to a relative’s house and one man helped us. He said, ‘No problem. You can stay in my house.’ My grandmother said to my father, ‘You should go to Europe. You can’t stay in the house. You can’t work in Iran. If they police find you again, they will take you back to Afghanistan and the Taliban will find you and kill you.’ My grandmother said, ‘You should go to Europe.’

“Six months ago we came by a boat to Lesbos. And now we are in Europe, but my father is very scared a lot and sad a lot. He still worries that the police here will deport him back to Afghanistan. And he worries about my grandmother and grandfather there.

“When we started this travel, we went through Turkey. There was water at the border. We stayed in the water for three days. Three days walking in the water up to my waist. I have a brother who is fifteen years old and a sister who is nine years old. And my youngest brother is four years old. He sat on my mother’s shoulder. And my sister sat on my father’s shoulder. For three days we stayed in the water. We did not get out because of the police on both sides of the border.

“When we finally did get out of the water, our clothes were very, very cold. My sister and my brother had a very high fever. We were so scared.”

The tragedy didn’t end there. Shortly after this interview, Nagia’s father was killed by a smuggler while trying to cross yet another border. She is currently settled in Greece with her mother and siblings.

James

11 x 14”, oil, $600

“We had a normal life in Afghanistan. I used to work in private security. We lived with my brother who worked for the Afghan National Police (ANP). He was a very honest and good officer in a very bad society full of corruption, murdering, drug cartels and mafia. He was offered money and was invited to exclusive places by an organized criminal group. They practice criminal activities such as kidnapping, extortion, fraud and murder. Since he did not accept these offers, he started to receive threats and be subjected to intimidation. He reported them to the Ministry of Interior several times but they did not do anything to protect him. In 2010, during a direct attack against him in his workplace in Kabul, two of his bodyguards were injured and one of the attackers died. My brother was condemned to 20 years in prison for a crime that he did not commit.

“In 2011, when I was coming back from work four men asked me to give them a ride and they offered me good money. On the way they suddenly attacked me. They attacked me from the back seat and someone held me by my throat and the others stabbed me in the head and on my hand 13 times with a knife. I still have the scars. They thought I was dead, so they left me on the road and disappeared. I lost consciousness. Some people found me and brought me to the hospital where I stayed for one week. The Police said that (the attackers were from) the same group that attacked my brother before.

“In 2012, my brother received a call saying that his son had been kidnapped. However, it was not his son, it was my son. I consulted my family about what should we do and we negotiated with the kidnappers on the phone, but after giving us only a few hours they killed my son and left his body in front of my house. He was terribly slaughtered and it always comes to my mind and makes me upset.

“In 2015, during the celebration of the Holy Day, some people knocked at our house door. When my brother opened the door, two gunmen opened fire on him. He was seriously injured. When he returned back home from the hospital and our house was full of people visiting him, two bombs exploded in our house, although nobody was injured. That day, following the advice of my family, all my brothers decided that we had to leave the country.

“I just want to live with my family. We never had economic problems there and money wasn’t important to me. The only thing that was important to me was to live in a safe place without any danger.”

James now resides in Greece, where he works as a translator and a driver, and volunteers with organizations that aid refugees.

Akhtar

11 x 14”, charcoal

Akhtar is a Palestinian Syrian from Damascus. He was an expert craftsman in marble and granite, and created luxury bathrooms and kitchens before war destroyed his business and home. His name is well known amongst many in his home country. Five stores. His life's work. All gone.

“We are Arabs from Palestine. I was born in Syria. My family came from Palestine then went to Lebanon, and then to Syria. I am 56 years old. I have five children, all young adults.

“In Syria, my sons were working and I was working and suddenly everything was gone. And everyone was separated. You didn’t know when you could die. Here is a mortar, here is shooting, here there is something. It’s a tragedy. A tragedy. The whole world can see what is happening in Syria. They are destroying the country until there is nothing left. Let me tell you something. I never in my life thought to leave Syria… If the Syrian conflict were to be resolved we would go back to Syria, we have no problem with that.

“You’re living like a king then suddenly you find yourself at the bottom. The war was happening all around us. The people were coming to us in the Yarmouk Camp seeking refuge. People were helping each other. Would you like to see your brother lying in the street, or your sister? No one wants that. Everyone in the camp was helping each other. All of Yarmouk, the Palestinian and the Syrian. We were all brothers and we helped each other. War is unjust. The whole Syrian nation is undergoing an unjust war. The whole Syrian nation has suffered.

“Evil exists and good exists and the evil has now become more than the good. Everyone is thinking about money. The government and leaders think everything is about money, but money is not everything. No matter how much money one gathers, tomorrow this government and leaders will all be gone. Where are the emperors that once existed in the Islamic state and the Persian and Roman empires? It’s all going to be gone.

“I have three sons still in Lebanon. A 30-year-old and a 29-year-old and a 28-year-old. I brought my youngest son with me because we are both alike and he couldn’t live there. If I had had enough money, we all would have left. I wouldn’t have left anyone in my family behind. We are asking for a humanitarian refuge. That is the first thing. After refuge, we will learn the language. We are not here to stay and become a burden to the German people. We are ready to work. Work is like worship. A most striving worker, as they say, is the one who works to feed his children and brings goodness to all his family.

“There is too much to say. All people should love each other. We are all from Adam and Eve and we are all connected and from the creator of this universe.”

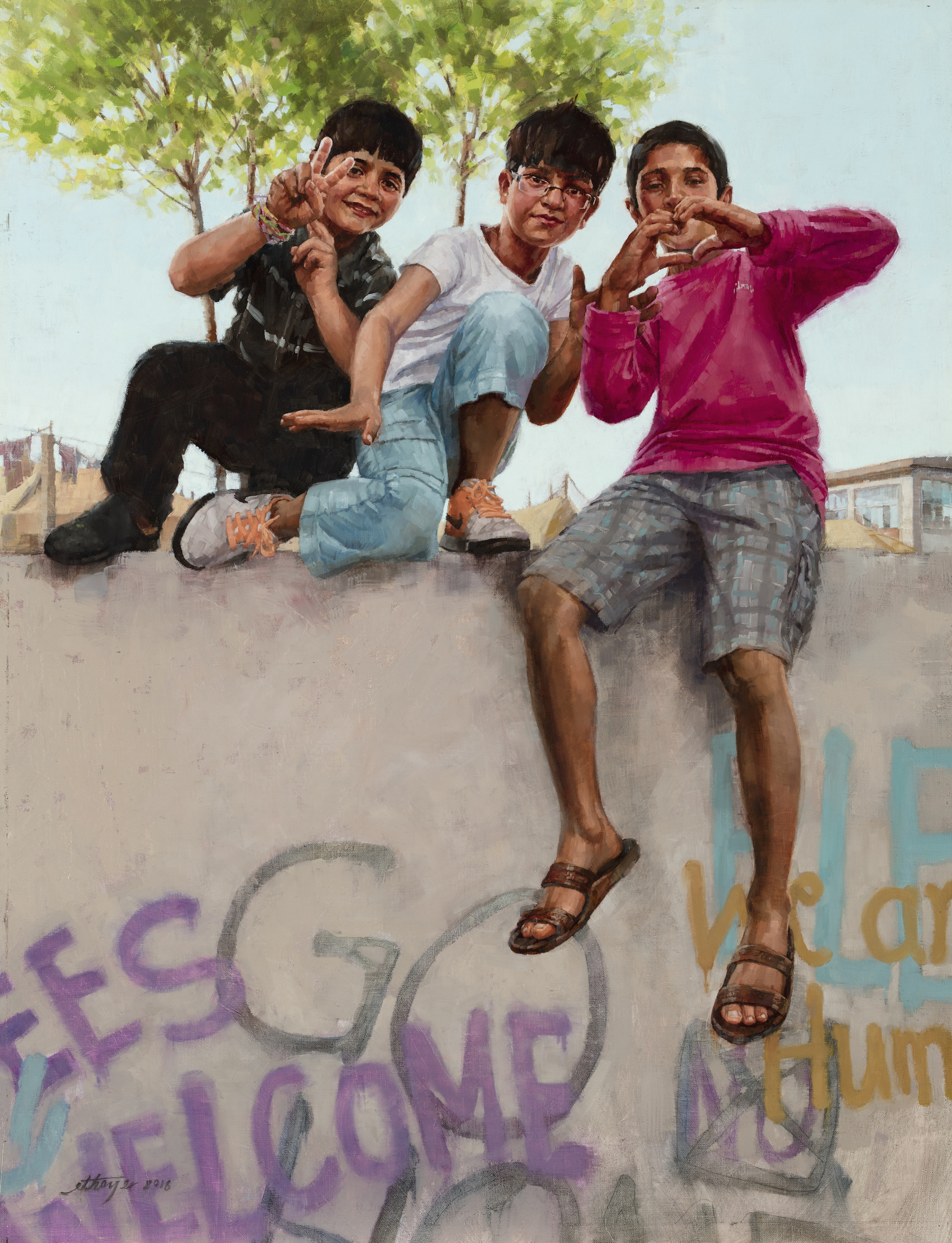

Message to the World

26 x 34”, oil

“The world is indeed full of peril, and in it there are many dark places; but still there is much that is fair, and though in all lands love is now mingled with grief, it grows perhaps the greater.”

—J.R.R. TOLKIEN, THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE RING

There are currently 22.5 million refugees in the world. Over half of them are children; hundreds of thousands of them are children traveling alone. They have fled violence, conflict, and intense persecution in the hope that the rest of the world will show some humanity.

Children are the first to see magic, the last to lose hope. Long after adults have given in to despair and cynicism, a child believes in that which is good and right. That is why in the middle of a dusty, abandoned factory-turned-refugee-camp in Greece, you can still hear laughs and cries, hear the patter of feet on the cement floor, and feel a tiny hand slip into yours. Despite all that has happened in their short lives, they are willing to trust, to make a new friend, to hope for love returned.

These three boys fled violence and persecution in Afghanistan, undertook perilous journeys with their families, and landed in the refugee camp in Greece where I met them. One of them, Isaaq, trailed me all day, wanting to play, laugh, hold hands, and watch me draw. The others scuffled in the dirt, took turns on the one bicycle in the camp, bossed the younger children, annoyed the teenage girls, struck endless ‘peace’ and ‘love’ poses for the camera, and generally got underfoot, all with the youthful optimism of a Cub Scout.

Their future is uncertain, and their past is gone forever. This precarious position could understandably inspire fear, mistrust, and despair. Yet so often it is the children who are able to rise above the rhetoric of fear and show us all what humanity really means.